The Houses

Dwellings for the citizens were built within the residential blocks delimited by the streets. The domus could be on a single or two floors, with rooms arranged around a columned courtyard.

At Libarna the first evidence of residential architecture dates back to the period between the end of the first century BC and the beginning of the first century AD. Remains were brought to light in large part of the so-called “amphitheatre neighborhood” and along the “theatre road.” Nowadays it is hard to understand the phases and arrangement of the houses, due to the fragmentary documentation provided by the excavations and also because of the spoilages carried over after the abandonment of the site.

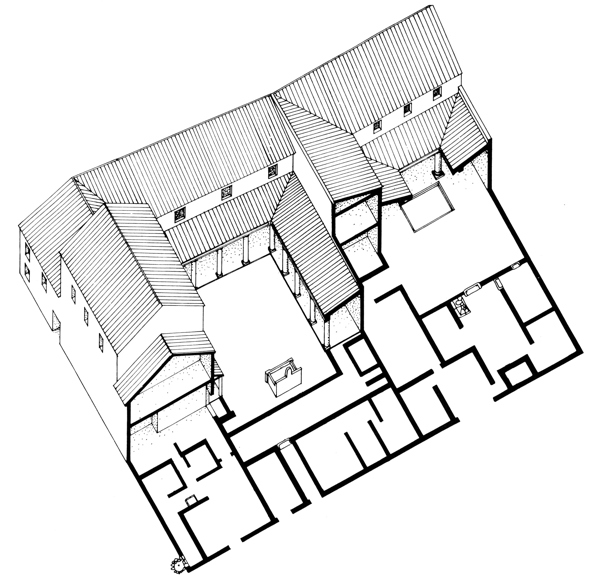

The first phase of the two blocks adjacent to the amphitheatre can be dated to the late-Roman republican/Augustan period (late 1st century BC – end of the 1st century AD). At that time each block was divided into a large healthy domus and three more modest dwellings with a partially covered courtyard and rooms with commercial function (tabernae).

At the end of the first century AD the blocks underwent a sort of architectural conversion, probably related to the construction of the amphitheatre. The two large houses with atrium and peristyle were divided into lots, while a requalification took place allowing for manufacture and commerce, with shops, workshops for wool dyeing (fullonicae) and a physician’s study.

Libarna never had a demographic growth that would justify the presence of dwellings on more levels destined to host several families (insulae).

Finds

The arrangement of the Roman houses

The Roman house was definitely different from contemporary dwellings, which are private spaces where the family lives protected from the public context. Nowadays the concept of privacy has even a legal value and the house provides little room for guests, work and business, a part from the limited cases of restricted groups of high society. The Roman house on the contrary was a centre of social communication and self-representation.

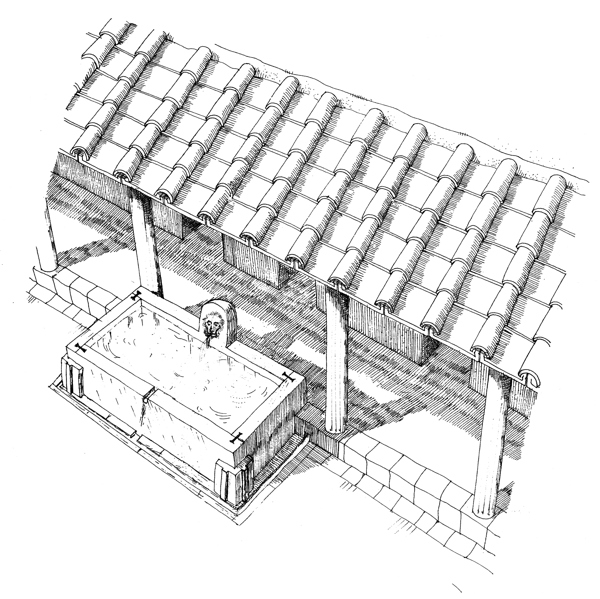

Leaving aside the purely functional spaces, the basic criterion for the spatial arrangement was the creation of a “path” within the representative sector of the house of an aristocratic family. After the access through the entrance (fauces), one would have entered the courtyard (atrium), which was the real focus of the layout of the aristocratic house. Then followed a sort of reception room, the tablinum, which also worked as a family archive; here the owner carried out his social relationships. Along this route the signs of the owner’s (dominus) social status were displayed. The atrium hosted the portraits of his ancestors (an evidence of nobility and family history) and the shrine of the Lares and Penates (deities protecting the family and the house in general). In the tablinum large wall paintings, inspired to great Greek artworks, enriched the owner’s self-representation with the importance of culture.

Furthermore the triclinium, that is a room for official meals, was again decorated with frescoes, mosaics and statues. The structure of the house was completed by rooms (alae) destined to various purposes, cultural spaces and bedrooms (cubicula).

Alongside the latrinae usually the kitchen (culina) was located, which was not necessarily a permanent feature, since it could in turn be arranged in one or another space. The path ended with a green space (hortus) in the typical house.

From the late Roman Republican age (end of the 2nd – 1st centuries BC), under the overwhelming thrust of Greek culture, one or more large colonnaded gardens (peristilia) were added, faced by the rooms destined to private use, where the owner and his closest friends could rest. In this sector of the house – as in the villas out of town, away from official public life – the owner could freely enjoy what the conservatives of the old republican traditions called the luxuria asiatica, that is the ways of life suggested by the Hellenistic courts and elites, considered as a sort of “upper world” .

The social structure of the aristocratic house therefore imposed a hierarchical path that led more and more inwards.

Also the middle classes, however, liked this model and yet mirrored it in their homes with more unpretentious means, by reducing the number, size and decoration of the rooms to the essential traits.

The lower classes lived in blocks of rented flats (insulae), bounded by streets, which typically carried the owner’s name (eg. insula Sertoriana).

Schematic reconstruction of the house atrium and peristyle (II block) and the adjacent lot B.

Italiano

Italiano Français

Français